Mendi, November 1950

As soon as Gordon Young heard that the MOM Board had approved their new mission, he was very keen to make a start. The next time Assistant District Officer Alan Timperley went on a patrol to Mendi from Mount Hagen, Young went with him. In his first letter from Mendi, Young wrote:

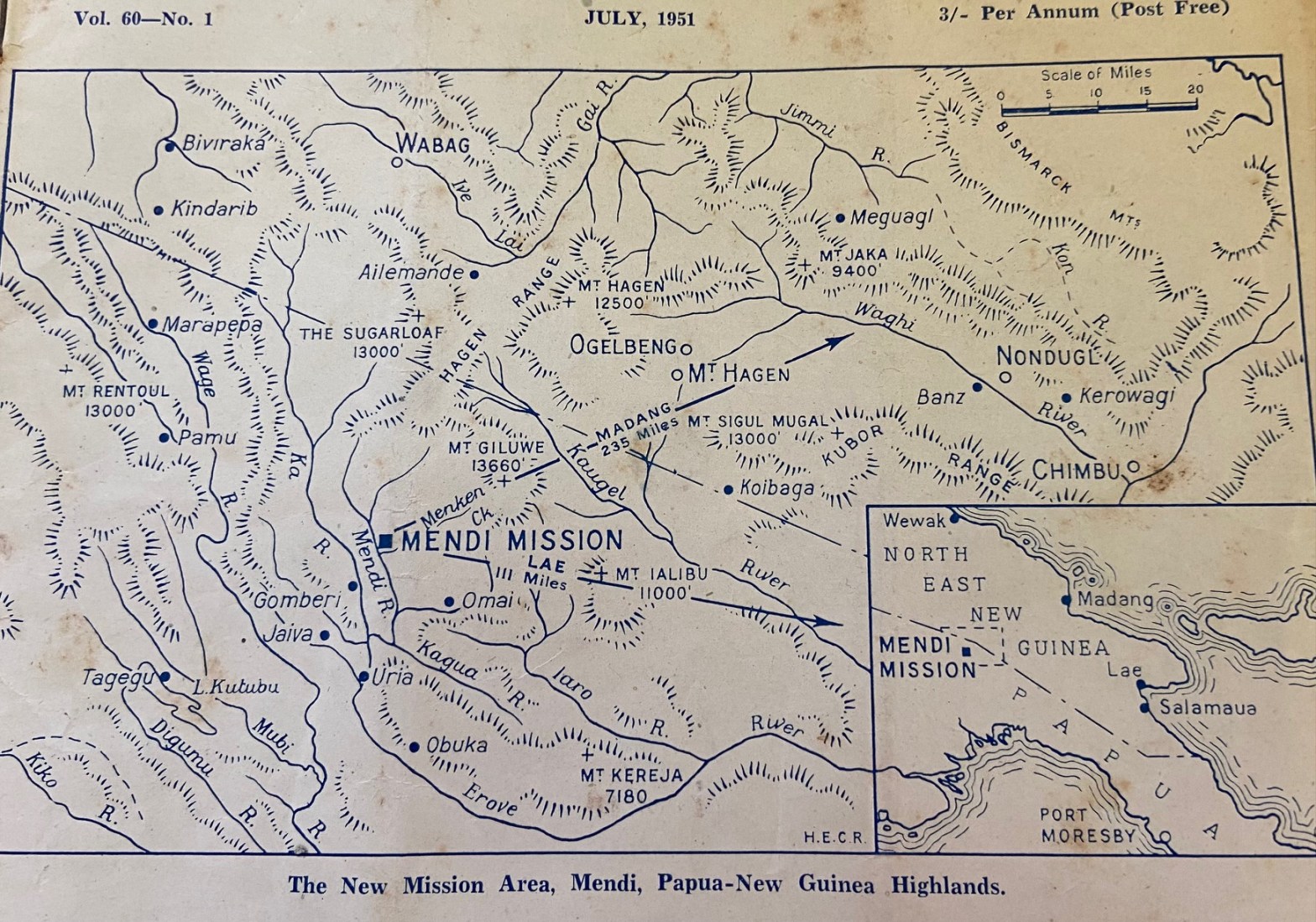

We reached here in Tuesday 21st instant,[21 November 1950] after a five days walk, without incident, from Mt Hagen. Tomas Tomar, David Bulu and I accompanied the Administration party; Kaminiel Ladi was sick the morning we left and will come in by Auster next week. The Auster was able to bring in two loads of cargo for us on Friday 17 November – 500 lbs per trip.

Rev Gordon Young, The Missionary Review 1951

Mendi Mission Station. The Officer in charge of the Administration Station at Mendi, Patrol Officer A.T. Carey, assisted me on Friday last to select the site for our first Highlands Station, and on Saturday we surveyed the five acres for the Mission lease, for which I will now apply. After this is granted, I will apply for two hundred and fifty acres Agricultural lease, adjoining the Mission lease. The A.D.O. Mt Hagen, Mr A.T. Temperley, who paid us a brief visit by air this morning, has approved of the site we selected, so we move there today. We intend building temporary buildings this week and next week to commence planting gardens; at the same time learning the language of the people.

For the first week, Young with Tomas Tomar, David Bulu and Kaminiel Ladi stayed with the men of the small government patrol post beside the new airstrip at Murumb. The patrol officers explained that, for safety, the new mission needed to be close to their patrol post. They also said that Young and his workers were not to travel more than 3 km from their base until they were given permission. They were worried about attacks from local Highland people. The new mission lease was at Unjamap on one side of the swift-flowing Mendi River, with the government patrol post on the other side about one kilometre away. One reason for this was that the patrol officers had discovered that the clan groups on either side of the river were enemies. They thought it best to share the benefits of the newcomers, with their valuable pearl shell, steel axes and other treasures, as widely as possible.

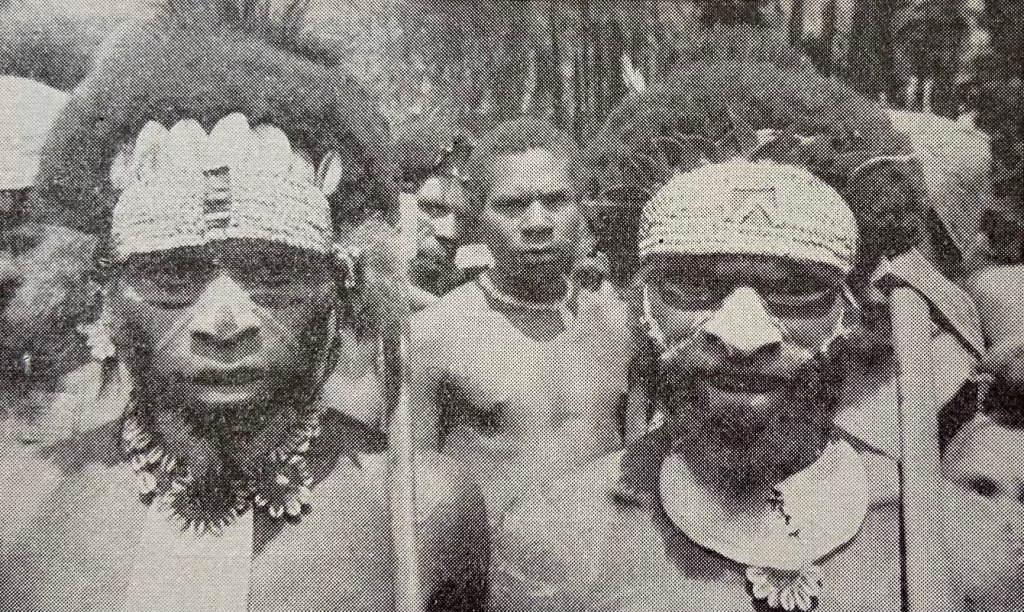

Kaminiel Ladi, David Bulu, Libai Tiengwa

In Young’s next letter, he wrote:

We commenced the establishment of this station on Tuesday last, 28th November [1950]. We have a quarter of the five acres cleared and some temporary buildings nearly finished. In the meantime, we are living in tents; mine is made of six lengths of unbleached calico for the tent and six for the fly, the ends being filled with kunai grass.

Rev Gordon Young, The Missionary Review 1951

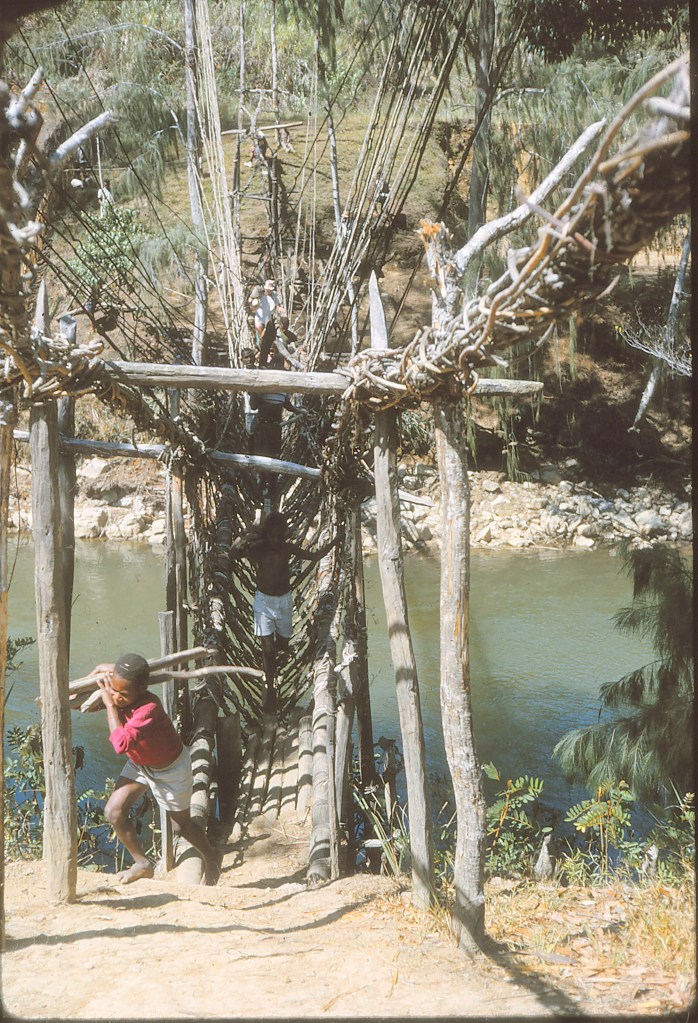

The local people saw the newcomers and the advantage of having access to some of their wealth. People had been paid for their work on the airstrip and with new buildings at Murumb. When the people on the east of the river saw that one of the white men and his workers were setting up camp on the west side of the Mendi River, they were not happy. One day when Gordon Young was visiting the patrol post on the east of the river, some warriors arrived to break the vine suspension bridge. When Young returned to the river, they found the vine bridge dangling in the river. They were cut off from their new mission lease. The people on the west side, the clans of Unjamap and Poromanda, led by clan leader Urum Tiba, were furious. If the newcomers were bringing wealth, their people wanted their share. Urum Tiba called for his people to come quickly, to collect timber and strong bush vines and to rebuild the suspension bridge. They worked so quickly and well that after five hours of hard work Gordon Young and his friends were able to cross over the river and go back to their new home. (Many years later, when the Highlands church celebrated the coming of the mission to their land, they loved to re-enact the story of Gordon Young and the broken bridge.)

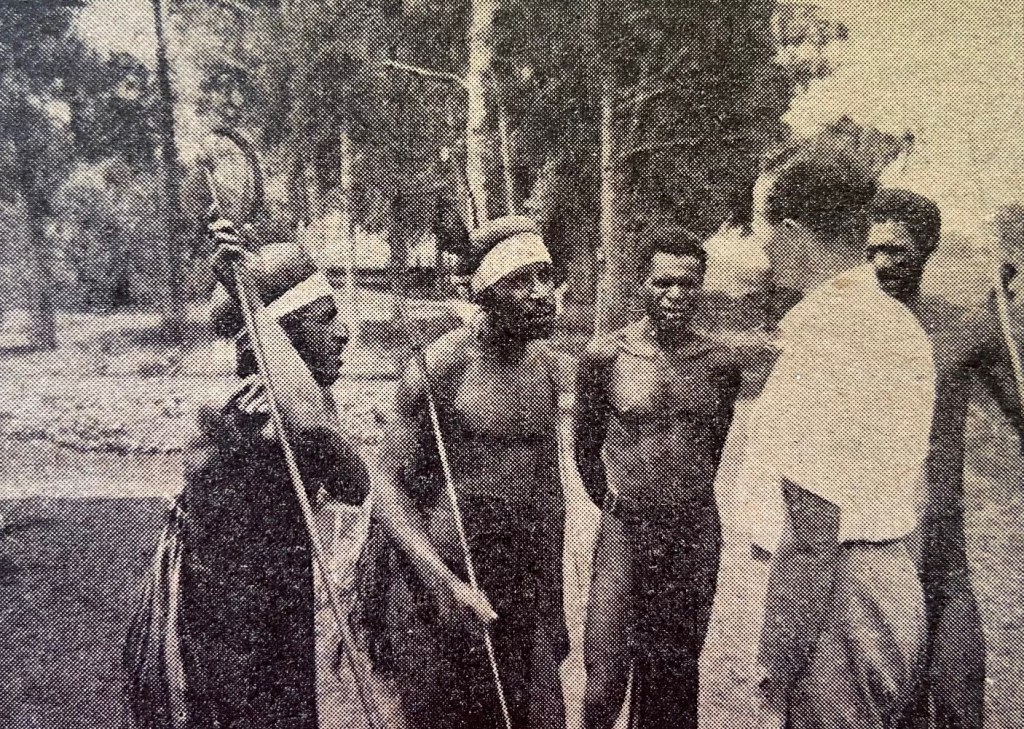

There were many misunderstandings in those early days of contact. The people of Mendi and the newcomers could not understand the language of the other. They watched each other and were puzzled and surprised at what they saw. What did this mean? Were these strangers the spirits of their ancestors come back to life? Were they dangerous?

The Mendi people did not understand what was going on. For six days, young men came to see the newcomers and were given spades and encouraged to help clear the land. They were promised axes or pearl shell for their work. But on the seventh day, the white man and his helpers did not bring out any tools. The Mendi men watched them. They were sitting on the ground together with their eyes closed, and talking. ‘Has their brother died? Are they sad?’ they asked each other. When the little mission group began to make a noise together, the Mendi men were sure that someone had died. To them, the sound they were hearing was the sound of sad wailing, not music. It would be some time before they understood that the newcomers did not do their usual work on the seventh day and that the mission group were praying and singing.

In his flimsy temporary tent of cloth and branches one night, Gordon Young did not know that he was being watched. Outside in the dark, a group of Mendi men armed with bows and bone-tipped arrows waited and watched. They were angry because one of their clan members had been arrested for stealing from the mission tents. Shadows moved against the cloth from the small hurricane lantern inside the tent. The warriors planned to shoot the stranger when he put out his light. They waited and waited but that light still shone. The stranger also had a small light on a stick and they decided that they would need to capture that, too. At last, they decided to go home and leave the stranger alone. Perhaps, they said, they would come back another day and shoot him.

As the little group settled in at Unja, Young wrote ‘The mission site is excellent for buildings but rather exposed for gardens. The prevailing southerly has been blowing strongly for the last few months. Hope to get more agricultural land across the river Mendi later’. Although they had little experience in first aid, Young ordered basic first aid and medical supplies as he hoped to open a hospital in the future. He did his best when people came to him with wounds from tribal fighting. He wrote, ‘Our first patient who had an arrow wound in the ankle—it went in one side and out the other—is now walking around without a stick and is one of our most conscientious workers’.

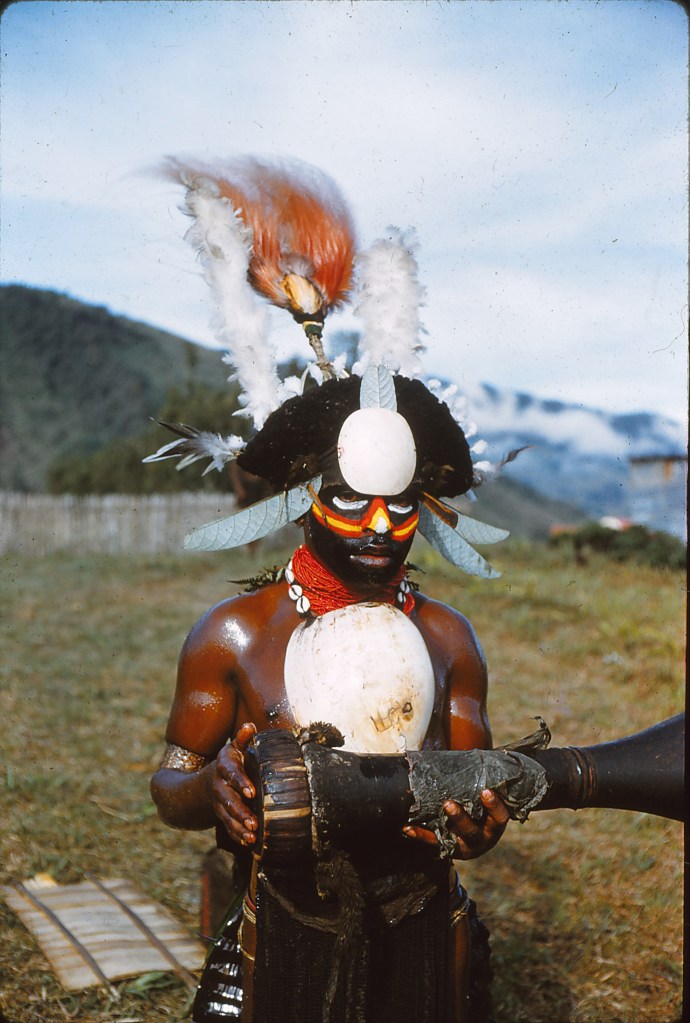

In March 1951, Young and his pastors heard news that there would be a great dance at the ceremonial ground near them. They thought that this dance would be for the people who lived near them. They had not seen a great singsing dance in Mendi before. They were very surprised when hundreds of people came to Unjamap, some of them from far away. They danced all morning. Young wrote, ‘The organised dancing continued until noon. An interesting feature of the promenades and circular dances being the way girls and young women were interspersed with the youth and young men.’ Gordon Young thought that this great dance was a sign that the people were happy that he had come and wrote

‘This celebration was to express the joy of our presence here, doubtless the first pay day on the first of this month, when they received payment in axes and knives for their services also the good quality gold lip shell they receive for sweet potatoes are factors which influence their primitive minds. However, the Christian living of native teachers is an effective witness among people untouched by the gospel.’

Rev Gordon Young, The Missionary Review 1951

Perhaps this celebration was a traditional dance that brought together many clans, and had been planned for a long time, but Young didn’t understand the meaning of it.

Six men from the island Districts were part of the team that made the first survey but by March 1951 some of those men had returned to their own Districts. The men who stayed were Tomas Tomar and Kaminiel Ladi. Libai Tiengwa went back to Papuan Islands but came back to Mendi later and served there for many years. Early in 1951, Daniel Amen and Sidni To Iara from New Guinea Islands joined Young in Mendi. The little group at the new place at Unjamap were very happy when two more new men arrived to join them in March 1951. Setepano Nabwakulea was a teacher from Misima Circuit in Papuan Islands District and Timoti Newai was coming to establish a pit-saw so that timber could be prepared for the new mission buildings. Soon after arriving in Mendi, Setepano wrote a letter about his first impressions that was published in the Australian Missionary Review. In part, he wrote:

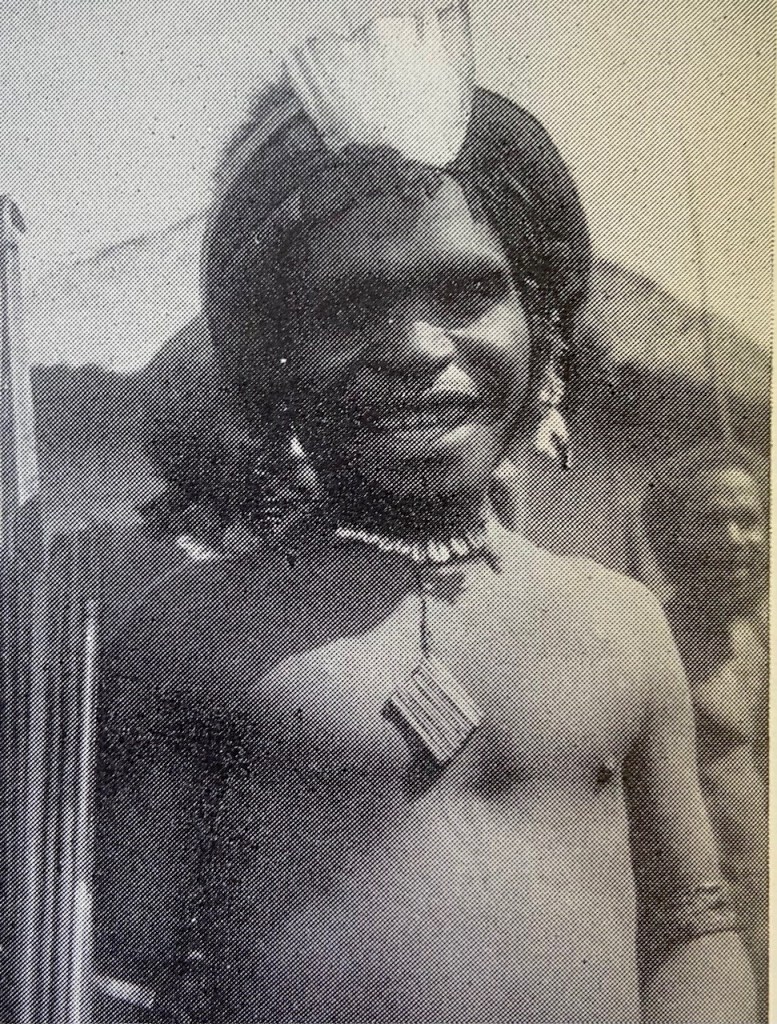

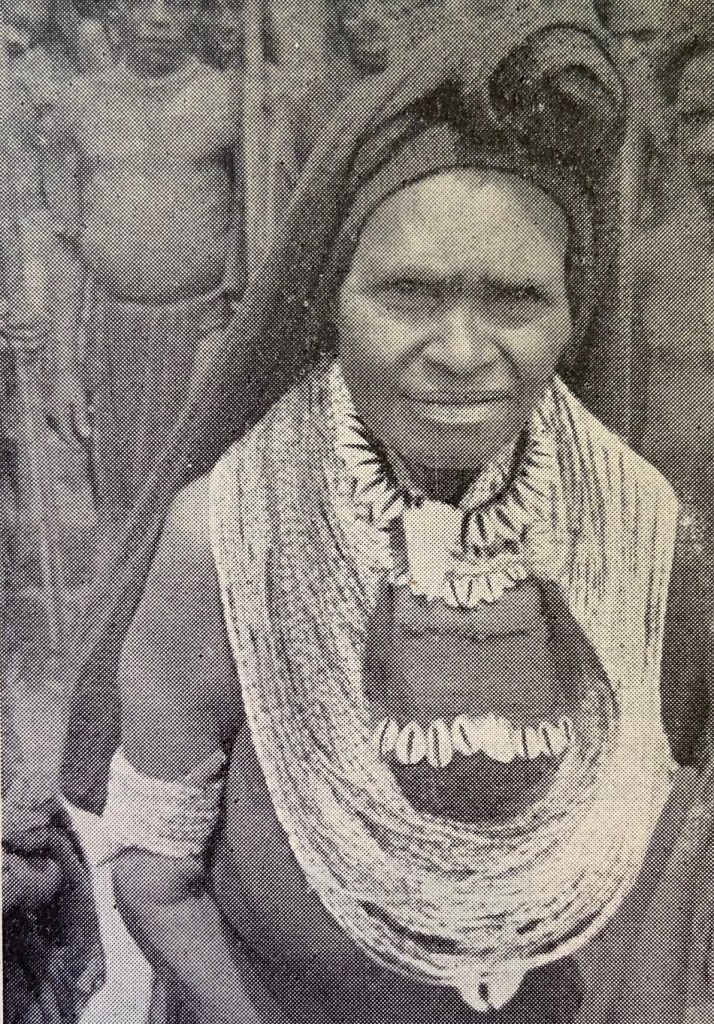

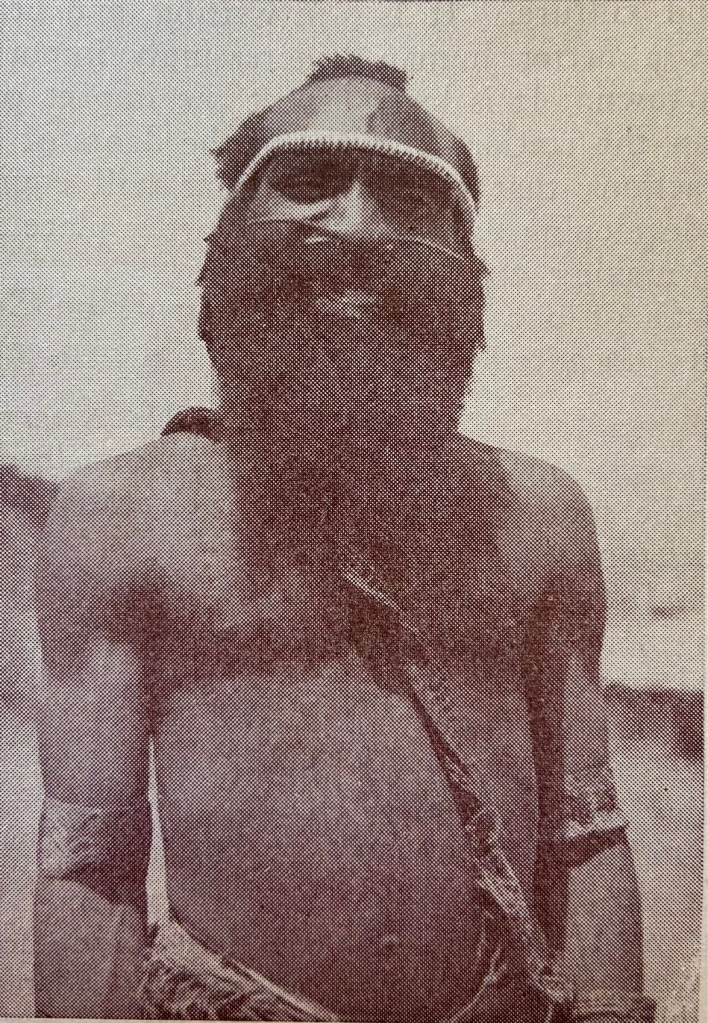

We were very surprised to see the new place and the men and women, also the different kinds of ornaments on their hair and bodies. They like very much something to see with their eyes and touch with their hands. Everything is new to them. They like the things from the sea and they use for their money a big shell called Gold Lip shell. They use many kinds of shell for ornaments. They still follow their old customs. The men carry spears or bows and arrows in their hands every day. When they walk about, they carry their fighting things with them. These men and women are still walking in darkness and their hearts are far away from Jesus. It is very hard for us to lead them out from the darkness into the light. But we believe the power of God can do this because everything is possible to Him.

Setepano Nabwakulea, The Missionary Review 1951

All these men from both Papuan Islands and New Guinea Islands gave many years of valuable and sacrificial service in the Highlands.

In the beginning, none of their wives were permitted to join them because the government did not think that it was safe. Gordon Young’s wife Grace Young was waiting at the Lutheran Mission at Ogelbeng near Mount Hagen, together with Muriel, wife of Kaminiel Ladi, Doris, wife of Daniel Amen and her sister Dulcie, wife of Sidni To Iara. These women had their own worries with health while their men were away. They all had great courage as they waited to go to a place that was unknown, strange and potentially dangerous.

Margaret Reeson 2023

Sources:

The Missionary Review January 1951, March 1951, May 1951, July 1951

The Methodist 5 May 1951; Rev John Dixon

Margaret Reeson, Torn Between Two Worlds, Kristen Pres, 1972 pp11-15

Elizabeth Priest Children of the Mendi Valley 1957.