- People who liked to fight

- A prohibited area

- Early medical work

- Catholic Mission in Mendi

- Observations of the Methodist Mission, 1954

People who liked to fight

By 1954, it was clear that there were many challenges for both the Australian government administration and for missions working in the Southern Highlands. Tribal fighting was one of many problems. When some people asked why missions were there at all, the MOM General Secretary Cecil Gribble replied.

“But behind all these problems are the more fundamental problems in man himself, and here the Christian Church has a part to play beside the Government. The Christian doctrines of God and man compel us to be there—of God and His all-inclusive interest in, and care for, the whole of His creation as shown once and for all in Jesus Christ and in His universal Word and atoning death; of man, and his power to rise to great heights and sink to low depths and his need of God— the God who was in Christ Jesus reconciling the world unto Himself. This is our Christian justification for being in Central New Guinea.” (Rev Cecil Gribble, MOM General Secretary)

The men of Mendi have always been quick to get into a fight. When they were not fighting each other and fighting enemy clans, in the 1950s they were attacking the Australian patrol officers when they came through their territory. One report said, in 1954:

“We were sorry to read the reports of still another attack on administration officers while on patrol in the Mendi area. This further report brings home to us the difficulty of bringing under control the people of these isolated areas in central New Guinea. Mendi is regarded by the Administration as one of the “trouble spots” of the area. In this recent attack natives ambushed the patrol as it was returning to camp and fired “dozens of arrows” into the ranks of the party. The Patrol Officer, Mr. F.V.G. Esdale, tried to protect the party without having to retaliate but when the attack persisted, he ordered the patrol to fire.”

A few months later, a new patrol officer was with a patrol led by Assistant District Officer Des Clancy. Nearly seventy years later, after the death of Clancy, Jim Sinclair remembered:

“I was posted to the Southern Highlands in November 1954 and for the first time worked under Des Clancy’s direction. We made one particular patrol together that I will never forget – arresting fierce Mendi warriors for tribal fighting. You get to know the worth of a man when arrows are flying.” (Jim Sinclair, patrol officer)

You get to know the worth of a man when arrows are flying. Jim Sinclair, patrol officer

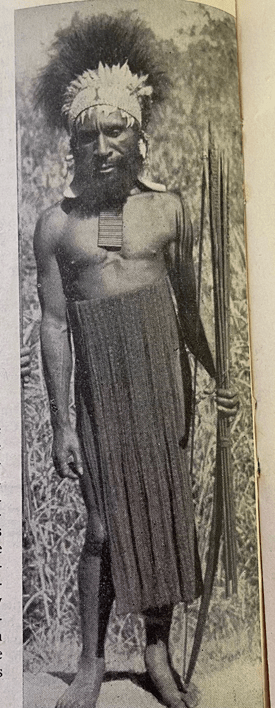

Clockwise from left: Mendi training with bows (Reeson 1962); Mendi man dressed for sing-sing (Reeson 1962); Mendi defensive fence with armed man (Smith 1963)

‘A prohibited area’

It was not surprising that the region was still a ‘prohibited area’ and any outsider who wanted to visit needed to have permission from the government. The Methodist Overseas Missions General Secretary Rev Cecil Gribble visited the Highlands again in 1954. He was very interested and later wrote several long articles for the mission magazine about his visit. In one of these articles, he wrote, ‘There are few more difficult places to administer in the world than the Trust Territory of New Guinea and the mainland and island chains of Papua.’ Climate, diseases, many languages, isolation, difficult mountain country, tribal fighting – all these things were challenging. That year of 1954 a major government patrol discovered a hidden valley in a remote part of the Highlands. The local people of that valley had never before seen people from the outside world. Some people started to say ‘Just leave them alone. Don’t disturb their happy life.’ Gribble admired the Highland people he had met. He wrote:

They are an active, virile, intelligent people.

“In many ways the people of the Highlands impress us with their gifts and aptitudes. In a healthy climate with sunshine, good rainfall and fairly fertile soil they have become amazing agriculturists and with the simple digging-stick and the stone adze they have cultivated their valleys with intelligence and skill, learning for themselves many of the things that we, too, have discovered by the processes of trial and error.

Their difficult languages they have evolved away from the contacts which have shaped the speech of the Melanesian and the Polynesian. Some of their implements of war, their ceremonial dress and their personal ornaments reveal a marked artistic sense. They are an active, virile, intelligent people.”

Rev Cecil Gribble , Methodist Overseas Missions General Secretary

Photo: Mendi man with bow (Missionary Review 1957)

But Gribble saw the damage of tribal fighting that went on and on, wrecking houses, gardens and lives. He also knew that the people of the Highlands were afraid of sorcery, witchcraft and the power of evil spirits. Life was not calm, peaceful or safe. A visitor told a story about visiting the Methodist Mission at Unjamap in Mendi one day. When he was walking back across the vine bridge on his way back to the government station, he met a crowd of people screaming in shock. A young woman had just thrown herself off the bridge into the churning river far below. The visitor was horrified to see the girl’s husband pull his stone axe from his belt and chop off his own finger joint in grief.

Gribble saw the value of many of the changes that were coming to Highland society. Law and order, health services, education, improved agriculture and a broader economy; all these things would be good. But he was prophetic when he added:

In all this development new problems will emerge. When steel axes replace stone ones, the wounds go deeper. When roads are made, insularity goes but diseases spread. When new and fertile lands are opened up, the European so often puts profit before the people’s welfare.

“In all this development new problems will emerge. When steel axes replace stone ones, the wounds go deeper. When roads are made, insularity goes but diseases spread. When new and fertile lands are opened up, the European so often puts profit before the people’s welfare. In all these things and many more, only a wise administration will show whether or not we are true to our trust in leading these people out into a fuller and better life. … For the Government there will be great and increasing economic, social and political problems which will be solved only with the best and most careful thought and action.

But behind all these problems are the more fundamental problems in man himself, and here the Christian Church has a part to play beside the Government. The Christian doctrines of God and man compel us to be there—of God and His all-inclusive interest in, and care for, the whole of His creation as shown once and for all in Jesus Christ and in His universal Word and atoning death; of man, and his power to rise to great heights and sink to low depths and his need of God— the God who was in Christ Jesus reconciling the world unto Himself. This is our Christian justification for being in Central New Guinea.” (Rev Cecil Gribble , Methodist Overseas Missions General Secretary)

Gribble was pleased to see what he called ‘on the whole a feeling of mutual respect between Government and Christian missions.’ The Minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, said of the inter-dependence of Administration and Missions, ‘We are, in effect, a working partnership in the special realm of human endeavour and activity.’

Early medical work

At the Methodist Mission in 1954, they were thankful that they were not attacked. Month by month, they were gradually earning the trust of the local people. The new young nurse, Sister Beth Priest, sometimes needed to treat people with arrow wounds, but more of her work was helping women with childbirth, accident victims and children with malnutrition. Beth Priest wrote:

“One night recently, when we were just about to settle to an evening with the language, news came to us that there was a young mother who was dangerously ill, following the birth of her first child. Knowing that it might be too late if we waited until the morning, the Rev. Gordon Young, Dr. Brotchie (who was visiting Mendi) and I, guided by our Mendi informant, set off to find her. For an hour we trekked through muddy tracks, up and over steep slippery hills, skirted on either side by trees and tall pitpit grass, until at last we emerged on to a clearing where the family house was built. A few yards from it, was a little temporary shelter where the husband sat. It was here that he had killed a pig that afternoon and now explained that his wife was better as a result! After a bit of persuasion, he led us to a small house where his wife was alone with the baby, custom preventing him from going to her. Dr. Brotchie and I had to crawl on hands and knees through the low doorway, and, once inside, we found that what the husband had said was true . . . only we did not give the pig the credit for it!

A wasted evening? Maybe! But by our obvious desire to help we had forged one more link in the chain of winning these folk to our Saviour. Some of the members of that family were present at Church on the next Sunday.”

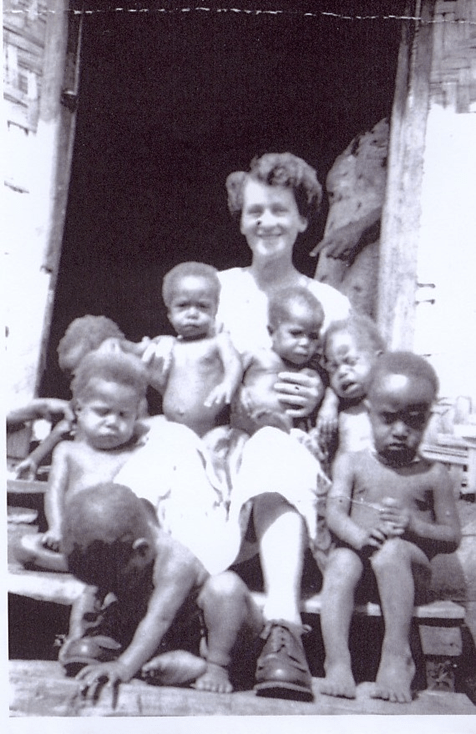

Among other work, Beth Priest offered a temporary home to several malnourished infants whose mothers had died. Sometimes a grandmother or the child’s father brought the child to the mission and were amazed and impressed to see that the nurse was able to feed the baby with a powdered milk mixture. At one point, six infants lived with the nurse and teacher until they were strong enough to go home to their families.

At one point, six infants lived with the nurse and teacher until they were strong enough to go home to their families.

At the end of 1954, Beth Priest sent home some excerpts from her diary.

August 22, 1954: David Johnston arrived back at Mission after a day’s preaching, with a “bag of bones” in the haversack on his back — a two-year-old girl, weight. 11 1b. 6oz., to add to our hospital family. (She is now an adorable, chubby lass, tipping the scales at 21 1b.)

September 30 : Elsie Wilson left for a month at Tari to help Rev. Barnes prepare a Primer and charts for the school.

October 16: 8 a.m., hearing wailing, indicating a death or “nigh unto”, David Johnston and I, plus four natives and stretcher, hiked to scene; man with pneumonia being “wailed to death”. Much heated talk; relatives were eventually persuaded to carry man to hospital. Funeral procession—tearful, hysterical wailing all the way! Anangol made amazing recovery; grudging gratitude by close of kin.

November 5 : Very ill five-year-old lad carried to hospital by parents from distance down valley. (Later, colossal amount of pus evacuated from areas around elbow and thigh; child recovered; splendid contact with this group of people.)

November 14: Evening. News of young man, known to us, fallen in river. Four of us followed our Mendi guide, almost at a run, up hill and down dale ( whew ! ! ) for half an hour. Arrived at house where we had previously found Anangol. This man, Tigit, still alive; had NOT fallen in river. Wailing almost deafening; pitch dark but for our lamp. Stretcher hastily improvised—no argument this time. Tigit’s mates shouldered stretcher and the wailing retinue headed for hospital. Decidedly eerie experience. (Tigit well enough to go home next day!) The Govt.-appointed “chief” of this clan, a young man, Benawi, given severe and lengthy instructions to bring sick people to hospital instead of going into mourning.

December 14: Benawi carried in his wife and child on home-made stretcher!! (Wife, too ill to walk, went home under her own steam five days later.) Perhaps this group of Mendis have at last learned their lesson, that we are their friends, here to help them.

January 7: Dr. Brotchie and I removed a two-inch arrow head (relic of fighting days) from man’s back, under local anaesthetic, while an apprehensive, then surprised, then delighted crowd of his friends gathered to watch.

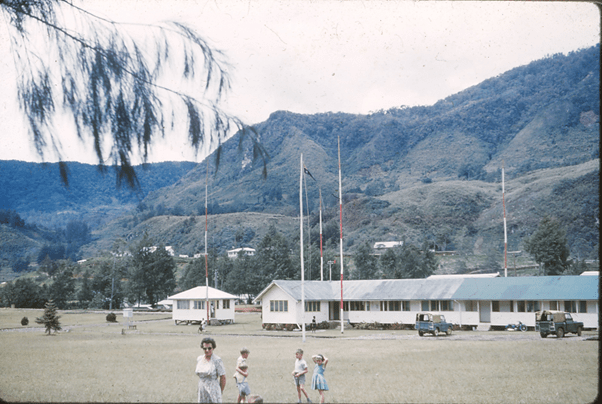

Already, within the small community of outsiders in Mendi, there was change by Christmas 1954. Since the day in 1951 when the Youngs entertained the three patrol officers and the small mission team for Christmas dinner, now there was a growing community. On New Years Day 1955, twenty-three European residents of Mendi plus nine visitors gathered to play tennis on the new tennis courts built by the kiaps. One of the latest arrivals was a young builder from New Zealand, Gordon Dey, the first of the promised New Zealand Methodists to arrive in the Highlands. Dey was to be responsible for the building of many of the well-built permanent buildings of the Methodists in Mendi, Tari, Nipa and Lai Valley for the next sixteen years. Among the visitors was Dr Brotchie who had been in Mendi to open the Methodist church building in 1953; he was so charmed by the Highlands that he brought his wife and three daughters for a three-week holiday there in January 1955. [Sadly, Dr Brotchie was killed in Sydney in August 1956. Someone, perhaps a person with a mental illness, placed a homemade bomb under the doctor’s car which exploded when the ignition was turned on, killing the doctor and his sister who was his secretary. This was a great shock and loss for the Methodist Church and for the support of mission.]

Catholic Mission in Mendi

One entry in Beth Priest’s diary read:

7 September 1954: Two Roman Catholic priests came to commence a Mission at Mendi.

It was not a surprise. Now that the rest of the world had discovered that a great many people lived in the Highlands, other churches wanted to start their own work among those people. In 1954, the leader of the Catholic Church for the very large area that covered the Western Province and much of the south coast of Papua sent two missionaries to visit Mendi and Tari for the first time. Their leader Fr Alexis Michellod MSC, a friendly man of many talents and deep faith, was finding out where the Catholic Church could start a new work. While Fr Alexis was visiting Mendi and Tari, an Archbishop was busy looking for one of the many Catholic Orders around the world who could come to the Highlands. Fr Alexis was getting ready to leave Tari at the end of his first visit when he received a message. It said, ‘Stay. Start foundation of Southern Highlands. Helpers coming soon.’

Fr Alexis found out later that an Order of Capuchin priests in United States of America were going to come to the Highlands. These men from the St Augustine Province of Pennsylvania had received an invitation from the Vatican in Rome. Would they be willing to send a team to the Highlands of Papua and New Guinea? It was a very long way from their home in America. But these men decided that God was calling them to a new work and very quickly, in two weeks, they agreed to be the pioneer Catholic group in the Southern Highlands. Because they were a long way away, and needed to prepare, the first of the team of Capuchin priests arrived in November 1955, Fr Otmar Gallagher OFM Cap. Soon the new men began missions in Mendi, Tari and Ialibu. In Mendi, they were welcomed to land at Kumin, just to the south of the little township and airstrip at Murumb, and started to build their houses, church and school. For the first year, the more experienced MSC missionaries trained the new Capuchin group, then left them to do their own work. In the same way as the Methodists brought Christian workers from other parts of the country, the Catholics also brought local workers from Western Province and Mekeo to share the new mission in the Southern Highlands. In those years, the Methodists and the Catholics didn’t have much to do with each other. Local Mendi or Tari people made up their own minds about whether they would follow one of the churches, or none of the churches.

In those years, the Methodists and the Catholics didn’t have much to do with each other. Local Mendi or Tari people made up their own minds about whether they would follow one of the churches, or none of the churches.

Observations of the Methodist Mission, 1954

One of the visitors to the Methodist Mission in 1954 was Rev Cecil Gribble. The first time he went to visit Mendi was in 1951, then in 1953 and now he was back again. Gribble wrote a long story about what he saw in Mendi in 1954. This is what he wrote:

“Flying in a D.C. 3 freighter from Port Moresby to Goroka one enters the more settled area of the Central Highlands of New Guinea and reaches country that for scenic grandeur must rank with the world’s finest. It is from Goroka that one goes west to Mendi and flies into what the Government calls a “prohibited area,” influenced by the Administration but not yet fully controlled by it. To enter this region, one must carry a special Government permit.

At 8.30 a.m. the little single-engined CESSNA plane of gleaming silver and red arrived at Goroka to fly me to Mendi. The ‘plane belongs to the Lutheran Mission and we owe much to the co-operation and friendship which this Mission has shown us in the pioneering of the Highlands Mission. The pilot, Bob Hutchins, is a young American of the Missionary Aviation Fellowship, which works with the Lutheran Mission in this country and serves any mission which needs its help. Hutchins gave me confidence in the care he took with every detail before we taxied to the take-off. I sat beside the pilot in this little machine which, as ‘planes go, seemed only a toy, and marvelled at the splendour of the country, the ingenuity of man, and of his faith that is actually removing mountains. We soared up to 10,000 feet over mountains, forests and rivers, grassy highland plateaux, razor-back ridges and down the great Wahgi Valley. Below, from time to time, there were the little hamlets so characteristic of the Highlands, sometimes built precariously, away up on the very knife-edges of escarpments. Range after range passed until we swept down into the Mendi Valley, over the Mission Station and on to the small strip which from the air looked no more than a cricket pitch scraped between the mountains and close beside the Mendi River. Pilots in New Guinea certainly need to know their business.

The Government Station at Murumb with the Australian flag flying beside neat native-type administration buildings had the air of officialdom. A mile away up a steep but well-made road the Mission has been established on a plateau with a magnificent view across the valley and then away to the distant north and south. The development within three years is surprising and high credit should be given the Superintendent, the Rev. G. H. Young, who has led this pioneering work.

Here is a striking establishment—church, school, hospital, mission houses. Paths link up the whole, lined with casuarina trees and shrubs. All the buildings are thatched with kunai grass and walled with the attractive plaited pit-pit or wild bamboo. The school is in charge of Miss Elsie Wilson, who is a born teacher with real insight into the educational approach to this primitive people. Inside, the walls are bright with simple but effective teaching aids and charts. They were strange classes, with both adults and children clad only in the string girdle with the leaves flung behind. Some had the coveted pearl-shell around their neck and a feather or two in their hair, old and young together.

But there was interest, the prerequisite of all real education, and one was not surprised that this school has received such commendation from official visitors.

The hospital, supplied with drugs and equipment by the Government, was under Sister Beth Priest, and although the people have not been as receptive to the medical work as we had hoped, lives are being saved, confidence is being built up, and in these clean, attractive, kraal-shaped buildings, men, women and children come under the skilful treatment of the Mission Sister.

One hundred acres or more have been brought under cultivation with the trained leadership of Mr. David Johnston. Not only have fine vegetable gardens been established but valuable experimentation in tea, coffee and other crops is taking place. A small herd of cattle is being built up. Impressive development has taken place in agriculture and the people’s interest in the crops introduced is growing.

Rising steeply at the back of the Mission is a range of 1,700 feet and at the top of this is the pit-saw under the Papuan missionary, Timoti, and his team of Mendi men. At 8 a.m. we set out to climb to the pit-saw through scrub and thick mountain forest up a grade so steep in places that we could only plant our feet in the imprints of those who had done it often. Looking back there were magnificent views over the Mendi Valley. We saw the preaching groves, where services are held regularly, and outside in the restricted area we were shown places where dangerous people live and where patrol officers have been surrounded and ambushed, and arrows and spears had come from hidden hands. We reached the pit-saw over the top of the range and were then 8,000 feet above sea-level. It was worth climbing to see Timoti’s pleasure at our visit. We returned home wondering how he faces this climb three times a week in order to come down to the Church meetings on the Station. These pastors from Papua and New Britain are in the true missionary tradition giving themselves without stint and doing a work that is invaluable.

A human sidelight was the waking one morning to find that thieves had broken into the store. They had dug a tunnel under the wall and come up under the pit-pit floor, taking one case thought to be filled with the much-prized pearl-shell. But the box held an electric fence bought for the cattle and as yet unused. The only clue left for the police was a few leaves from the clump that the people wear behind them. Alas, these few “tail feathers” would not tell much to either police or missionaries. The case and the fence were found later, discarded, but whole, in a patch of kunai grass.

While at breakfast, two fearsome-looking men with blackened faces and bows and arrows came to the mission house. Their country was over the ranges in the Lai Valley, where administration officers had not long ago been attacked. They asked that missionaries be sent across to live amongst them. Perhaps it was the pearl-shell and the trading goods that made some appeal, but perhaps, too, there was real desire for something better.

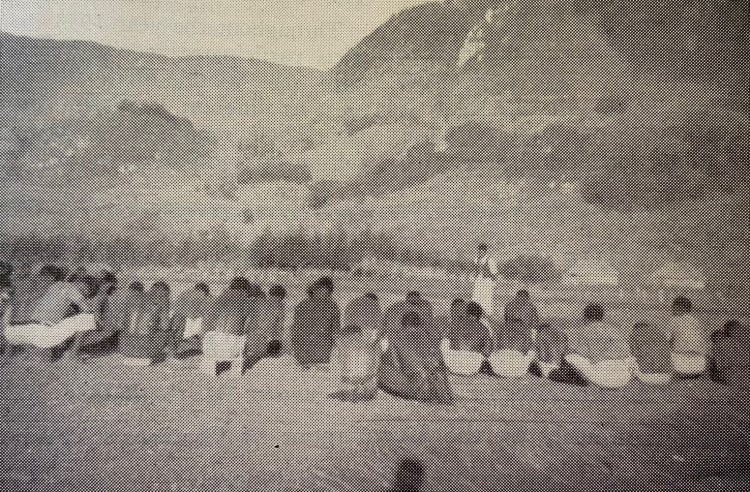

On Sunday, the patrol with the preaching services in the hamlets was for me an unforgettable experience. First down to the air-strip where the Rev. G. H. Young and Setapano, the Papuan pastor, gathered the people from the Administration quarters. As the sun rose over the mountains there was prayer and a simple story from the New Testament, in pidgin English for the police and cargo boys who had come up with the Government from the coast, and in Mendi [language] for the people of the Valley. It was a New Testament situation: mountains on all sides, the blue sky above us, bright morning sunshine and a young Papuan speaking about the things of the spirit which he had found true in his own life. We walked on over the hills to Wagwag and other places, meeting people on the road, men with feathered head-dress, axes over their shoulders, bow and arrows in their hands. Women working in the field joined us and sat with us in the little cleared ceremonial grounds that go with each hamlet and which are surrounded by groves of casuarina trees. Strange congregations! A woman with a pig under her arm, a man with burning charcoal to light his cigarette, an old wrinkled, skinny woman eating a baked sweet-potato, chattering children. But when the preacher told a simple parable there was a real attempt by them to follow and understand. Week by week the missionaries go out two by two into the surrounding countryside, bringing to people this message which they have come to call the “good talk”. To think about it is to know that out of this embryo situation will come the Church victorious.”

Week by week the missionaries go out two by two into the surrounding countryside, bringing to people this message which they have come to call the “good talk”. To think about it is to know that out of this embryo situation will come the Church victorious.

Margaret Reeson 2023

Sources:

The Missionary Review—April 1954—Page 15

Jim Sinclair, Tribute: Recollections of Des Clancy, Admired Kiap, 8 February 2020 Una Voce

Elizabeth Priest, The Missionary Review—April, 1 9 5 5 — P a g e 6

Cecil Gribble, The Missionary Review—May, 1954—Page 13

Cecil Gribble, The Missionary Review—December, 1954—Page 6-7

The Missionary Review— August 1954—Page 2

Central Queensland Herald (Rockhampton, Queensland) 16 August 1956 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/79267391#

Bishop Stephen Reichert OFM Cap. ‘A Short History of the Mendi Mission’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Catholic_Diocese_of_Mendi

Cecil Gribble, The Missionary Review October 1954