Our missionaries are doing a great job but, if their numbers were doubled, they would only be touching the fringe of this field. Rev Harry Bartlett, visitor to Highlands on behalf of MOM 1960

The cutting edge of the church’s advance is the witness and work of the island missionaries. Missionary Review March 1958

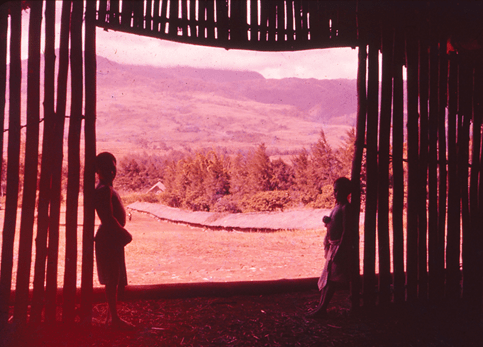

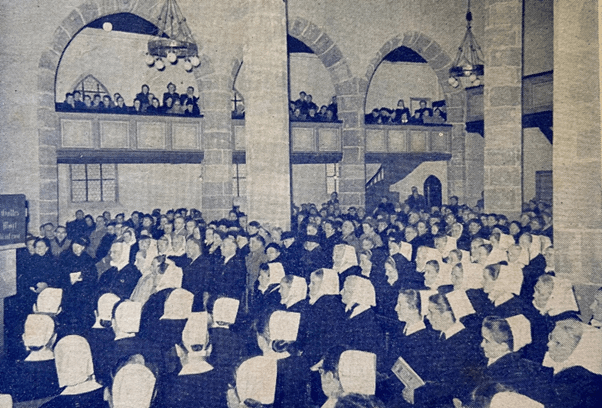

The rain was pouring down that night. It had been raining for days and now water was leaking through the thatched roof. The people in that room were very tired. They had been meeting all day. It was late at night now but they were still not finished. The Methodist Quarterly Meeting in Mendi was at work in September 1960.

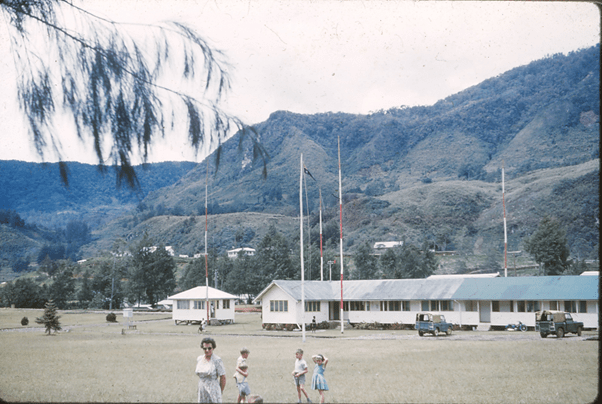

Some things were going well but they also had some big problems. They were feeling happy about some things. In the annual report from the Highlands for 1960 they were able to report on the beginning of the new Methodist mission in the Nembi Valley at Nipa to the west of the Lai Valley. At last, the government officers said that it was safe enough for them to start a new mission in that place. That was good.

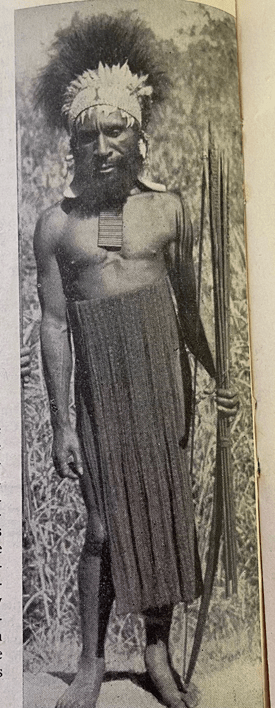

It was not so good that there was very little progress in their main work. They had come to introduce the good news of Jesus to the people, but not many people were interested. In Mendi, many of the men were very busy with everything to do with the cycle of Timb cult activities, with planning for big exchanges of wealth and the secret spirit business. In Tari, at the time when the mission was preparing for their annual Thanksgiving Day, many of the local people were more excited about the traditional mali sing-sing as they prepared for the initiation of young men. The new minister John Rees described the crowds of thousands of excited people with beautifully decorated dance groups. He wrote:

At 2.30 am the next morning we went to the Tege house, specially constructed for the initiation where we watched part of the initiation. A platform ran down each side and a long fire was lit along the centre. Men stood on the platform with bundles of switches and, as at regular intervals, a boy ran down the centre over the fire, the men chanted and struck him with switches.

The mission staff in Tari were working hard on language learning and had translated Bible lessons in Huli language for use in the Sunday Schools and day schools, as well as stories from both the Old Testament and New Testament into simple English. The teacher in Tari, John Hutton, wrote that a few of the school students were ‘thinking seriously about the claims of Christ.’ In Mendi, a few people attended literacy classes there but not many were very successful. David Johnston was doing his best to translate the Gospel of Mark, and David Mone was also doing some translation, but both of them were having problems with finding the best way to spell the words.

Now, on that wet night in September 1960 in Mendi, they were happy that, at last, a few people were starting to ask questions about following Jesus Christ. The first people to become Christians in Mendi were a medical orderly, Wasun Koka, an older school boy, Sondowe, a school girl Wesi, and Tundupi, a senior man from Kamberep. The members of that church meeting were very happy to agree that these people could start preparation for baptism. David Johnston was really happy about all of them. He knew Wasun well and also knew Tundupi from Kamberep. When a pastor was first stationed at Kamberep the local people did not want to welcome him because they had bad experiences with other outsiders. Johnston remembered sleeping there ‘in a camp full of fleas, flies and dust and being surrounded day and night by Mendi people of all shapes and sizes. They insisted on poking inquisitive faces into the camp no matter what I was doing. It was a pleasure to compare those days of unfriendliness with the present friendliness and honest openhearted welcome’.

The mission staff were happy about the new Christians, but they had a problem. Who was going to help these new Christians? Just when they were needed most, a number of experienced staff were leaving the Highlands at the end of their time of service.

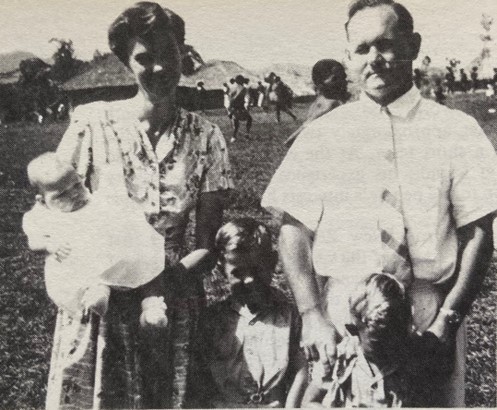

At the beginning of 1960 there were five overseas ministers working in the Highlands; Young in Mendi, Barnes in Tari, Keightley in Nipa, Mone in Lai Valley and newcomer John Rees who planned to go to a new station out of Tari. There were also mission teachers, nurses, builders, an office secretary and an agriculturalist from Australia and New Zealand. They all knew that the mission families who had come to the Highlands from the coastal regions to work as pastors were very important to the work. When a visitor from Australia, Rev Harry Bartlett, was in the Highlands that year, he reported that ‘Our missionaries are doing a great job but, if their numbers were doubled, they would only be touching the fringe of this field.’

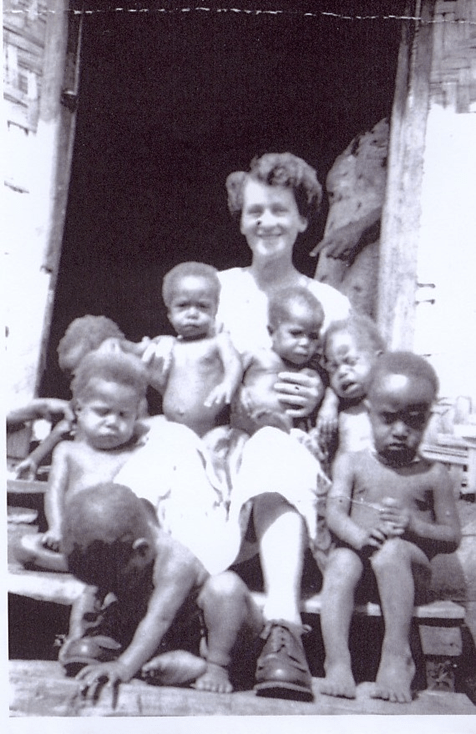

The visitor Harry Bartlett was correct to say that they needed more staff. The annual report for 1960 masked the real situation. When it stated that ‘thirty-five missionaries serve in the Highlands’, only eight of those came from Australia and four from New Zealand. Twenty-one of the mission staff were the excellent men from the islands of New Guinea, Papua and the Solomons. These men and their families were faithful, courageous, hardworking people who had chosen to live sacrificially in isolated and demanding places. But their education was very limited and none of them had been given key leadership roles at that time. It was very different in other mission districts under the leadership of Methodist Overseas Missions in Australia. In 1959, for example, there were 34 Australian members of staff working in Aboriginal communities in North Australia compared to seven in the Highlands. In other Pacific Districts there were far more Australian clergy than in the Highlands and they shared the work with large numbers of trained local staff. That same year, MOM invested just under £200,00 (like $7 million Australian dollars in 2024) in North Australia and just over £14,000 (like $493,000 Australian dollars in 2024) in the Highlands District. For a new mission trying to establish its work, perhaps it seemed that they were not being taken seriously by their sponsors.

In 1959, they had a small staff team. By the end of 1960, the team was even smaller. There were only two ministers left and other pioneer workers who had learned the language and had experience had also gone back to their homes. Gordon Young in Mendi went on leave in February 1960 but retired in October and did not return to the Highlands. Roland Barnes in Tari became very ill and was evacuated to Port Moresby and then to Queensland during 1960; he was not able to return to Tari. David Mone, after many years of missionary service, returned to his home of Tonga at the end of 1960. Cliff Keightley was the only minister left with any experience in the Highlands and he was very busy as pioneer of a new mission at Nipa and now as Acting-Chairman. The new man, John Rees, had only arrived in the middle of 1960. Now, instead of going to a new place in the Tari area, he was sent to Mendi to fill the unexpected vacancy left by Gordon Young.

As well as the loss of ministers, some of the pioneer group to Mendi, who had been learning the language and getting to know the people, were also going back to Australia. Teacher Elsie Wilson left in 1957 and nurse Elizabeth Priest left to be married the same year. The latest one to leave was David Johnston, who was leaving the day after that September Quarterly Meeting in 1960. It was very sad but true; the team at Mendi had not been happy together for some time. It was hard to work and live together when they did not agree with each other and often upset each other.

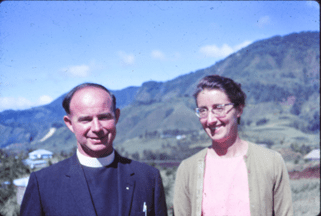

There were so many changes in a short time. The biggest change was that both Gordon Young and Roland Barnes left the Highlands in the same year, 1960. Nobody was expecting that. For nine years, Gordon Young was their leader and reports said that he had ‘carried the main burden and given outstanding leadership’. When Gordon and Grace left Mendi in January 1960, they looked forward to attending a big church conference in Melbourne and then going on a long trip overseas. Rev Roland Barnes was going to be Acting-Chairman while they were away. They did not know that Roland Barnes would be sick and have to leave the Highlands, too. They did not know that they would not return to the Highlands for ten years.

Something seems to have changed. Perhaps Gordon Young was beginning to feel tired and discouraged. He had been working hard ever since his first long walk into Mendi with the patrol officers in 1950. The local people were not interested in his message about Jesus Christ. The language was complex and he was still not fluent in speaking it. He had walked so many miles over mountains and through rivers and mud, trying to make contact with people, but they seemed to him to be stubborn and only interested in material wealth not in the wealth of the spirit. There were times when it was much easier and more rewarding to put his energy into working with the Australians who were working in the region as patrol officers, medical officers, agriculturalists, engineers and the rest. He joined the committee of the local Mendi Valley Club in the small township and was welcomed and popular there. These men appreciated his background as a Rat of Tobruk and soldier, and his work as chaplain to captured Japanese soldiers in Rabaul in the immediate post-war period. Gordon and Grace had always offered hospitality to the patrol officers in their home, from the first pioneering days.

He became more and more discouraged and despondent about his mission work. Even though a new secretary, Joyce Rosser, came from New Zealand to help him with the correspondence and other secretarial work, and he had a new office building, he seemed to lose interest in the daily work. Even when the latest new mission was opened in Nipa, he walked across the mountains from Mendi to Nipa with the minister who was to pioneer this new work, Rev Cliff Keightley, but left again after two days instead of staying for a few weeks as he had done with earlier new mission stations. Young decided that he would take responsibility for the mission finances, but found this job quite difficult and the financial records were sometimes in a muddle. A member of staff recalled finding him in the mission office with other work incomplete, tidying his paper clips and rubber bands.

In a staff meeting after the Youngs had gone on leave, his colleagues made a decision. They sent a recommendation to the Mission Board. When Gordon Young returned to Australia after his overseas trip, they suggested that it would be better for him, and for the work in the Highlands, if he moved to an Australian ministry as a fresh start.

In October 1960 the MOM Board announced that Rev Gordon Young had retired from mission work. Perhaps, looking back, Gordon Young was the right person for the tough, physically and mentally demanding work of the pioneer. A man of great physical strength and courage, he was able to achieve heroic feats of long mountain patrols on foot, travelling to places and facing dangers that would have defeated many others. Perhaps the time was right for change as the work moved into the next stage.

Ten years later, in 1970, he and Grace Young were welcomed back to Mendi with honour for the twentieth anniversary of the Church, as the pioneer minister. During that visit, he was invited to baptize a group of new Christians, a privilege he had not experienced in his long years of service. Gordon and Grace returned for other anniversaries, including the great event in 1990 to celebrate forty years. Still strong and erect at 78 years of age, Gordon re-enacted the legend of the time when he walked back over the repaired vine bridge to Unja in 1950.

One of the special ceremonies at the 20th anniversary was the unveiling of a memorial plaque at Unjamap. A big crowd of people walked together up the hill to Unjamap to watch. Gordon Young, with the help of his first partners in the mission in the Highlands, Pastor Kaminiel Ladi and Pastor Tomas Tomar, unveiled the memorial stone together. The two pastors from New Ireland served the church in the Highlands for more than twenty years. Gordon Young said, ‘Put their names first on the memorial plaque.’

Rev Gordon and Grace Young never forgot the people of Mendi. Back in Australia, he made a further contribution as chaplain of Prince Alfred College, Adelaide, held senior positions with Better Hearing Australia and was awarded RSL ANZAC of the Year Award in 1990. Both Gordon and Grace Young gave extended interviews to people who were writing the stories of Mendi in ‘Torn Between Two Worlds’ (Reeson 1972) and ‘A Bridge is Built: a Story of the United Church in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea’ (Wood and Reeson 1987).

After their deaths, the ashes of Gordon and Grace Young were returned to Mendi, where they are remembered with great honour and respect. Their memorial stones are at Unjamap, near where they lived when they were pioneers from 1950.

Rev Harry Bartlett, Missionary Review January 1961

Margaret Reeson, Torn Between Two Worlds, Kristen Pres, Madang 1972 p.61

Missionary Review July 1957 p.11

Missionary Review July 1957 pp2-4

Missionary Review March 1958

The Open Door Vol.50 No.2 September 1970 pp.9-10

Joyce Rosser, Missionary Review January 1960

Missionary Review February 1959

Missionary Review March 1961